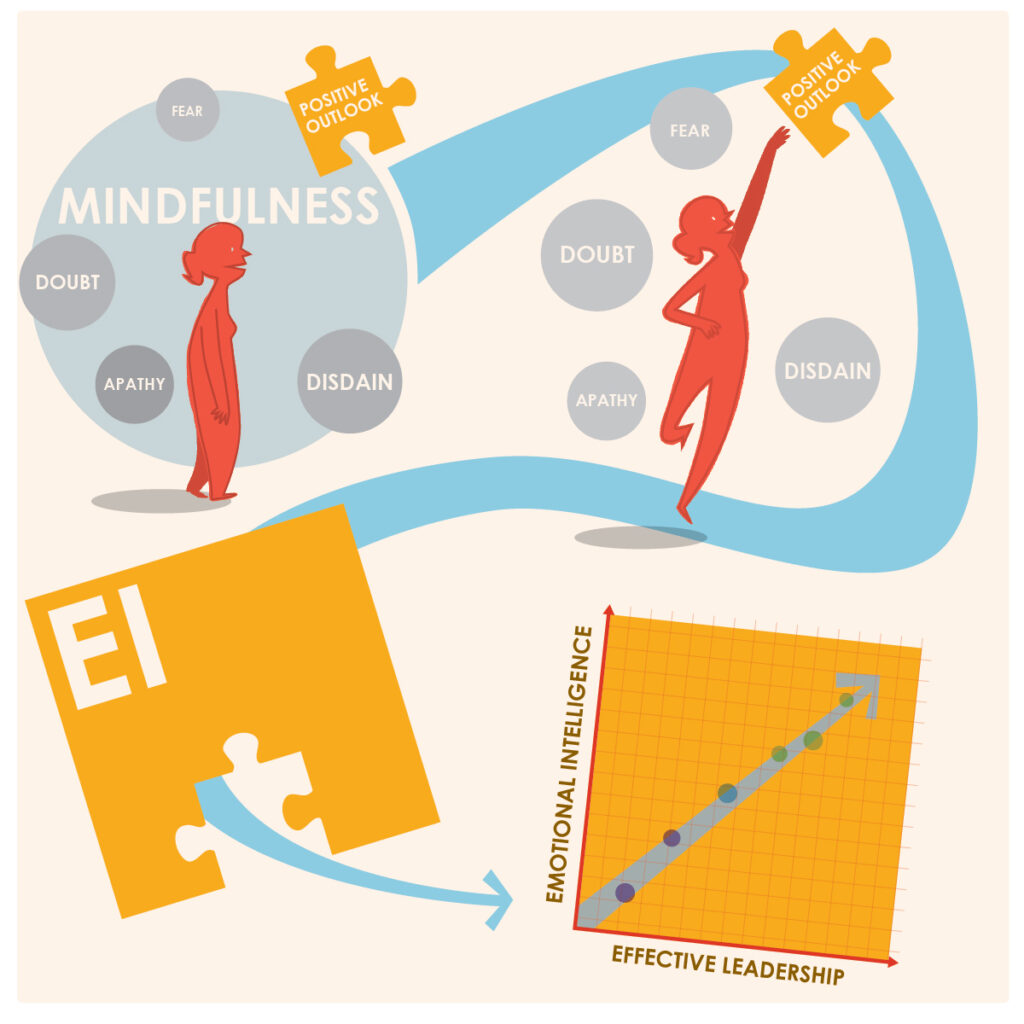

As leaders or managers we often find ourselves in a reactive frame of mind when we are under a great deal of pressure from self or external sources. Remaining in this reactive state can cloud the mind, diminish creativity, or isolate you from your team, and it is not conducive to an effective response to the situation. Developing a degree of self-awareness so you can notice your tendency to move towards a reactive posture in the moment – and consciously choosing to shift to a more interactive mindset – is essential in a leader.

In my early 40’s, I was involved in an interaction that served as a transformative experience in my development as both a manager and leader. The experience involved shifting from a reactive to an interactive mindset.

I was working as a CFO for a small company that manufactured ski-tuning machines in Waitsfield, VT. We were in the process of negotiating the sale to a much larger company. As is often the case in situations like this, I was negotiating the sale, but was going to lose my job as the acquirer already had a CFO. I was under a great deal of pressure both in negotiating the deal and in figuring out what I was going to do next. My wife, Patty, worked as a house manager in a respite house for people on hospice. She worked the 4pm to midnight shift. Most days we had transitional childcare to cover any gaps in my being able to get home to take care of our two children and and Patty having to leave for work. Transitional childcare wasn’t always an option, and on this day, with the sale looming and pressures building, I had to get home early because the sitter was only able to stay for a short while.

When I got home I paid the sitter and tried to get the kids gathered, focused, and out to the car to get one of them to an appointment. I was running late. Trying to get them out of the house with whatever stuff they needed wasn’t working. I was getting frustrated. I’m normally a fairly soft-spoken person, not inclined to lose my temper unless pushed, but on this day and in this moment I felt pushed beyond my limit.

I can remember the moment as vividly as if it were this morning. Kids churning in the kitchen, leading me to yell in anger, and then it happened. My son stood in front of me, my daughter just behind him and he said, “Poppy it’s not okay for you to talk to us like that!” It was as simple as that.

In my childhood, a response like his would have gotten me a slap across the face and an admonition not to “talk back” to my parents. For reasons I will never understand, I experienced what I can only call a moment of grace, of emotional self-awareness, a moment between hearing and reacting in which I realized he was right. I said, “You’re right. It’s not okay for me to talk to you like that.” I sat down on the floor and shared with them some of the pressures I was under, and in sharing I was careful not to ask them to take care of me. I just wanted them to understand that there was a lot going on and I needed their cooperation. It wasn’t about them, but in their frenzied state they aggravated my stress. What happened next was also a surprise. They both looked at me and he asked, “Why didn’t you tell us?” They jumped to their feet, ran upstairs, gathered their gear and were out the door and in the car in minutes.

I’ve thought about this often over the years. In our roles as leaders of organizations we are often under significant and unshared pressures from a variety of sources. As with my kids, it is important to be clear with those around us that it isn’t their job to take care of us. That’s our job. But we can share with our teams when we need help, or support. This is as important in a leader as in a co-worker.

Two aspects of this have always stood out to me in this illustration. One, the courage it took to speak up, and second, the importance of self-awareness. There are appropriate times to acknowledge a non-productive situation, and shift to an interactive posture.

While our management positions give us power and authority, they will never make us leaders.

The choice to listen and hear the opinions of others while under pressure and being able to have an open and interactive mind, sharing the pressures you are facing with your team, empowers them to participate in solutions.

Recommended reading:

Our new primer series is written by Daniel Goleman and fellow thought leaders in the field of Emotional Intelligence and research. See our latest release: Empathy: A Primer for more insights on how this applies in leadership.

Additional primers so far include: